Graphene from recycled tires to enhance properties of concrete – Rice University research

According to recent media release, Rice University lab’s optimized flash process could reduce carbon emissions, which could be be where the rubber truly hits the road.

Rice University scientists have optimized a process to convert waste from end-of-life rubber and tires into graphene that can, in turn, be used to strengthen concrete. The environmental benefits of adding graphene to concrete are clear, chemist James Tour says.

“Concrete is the most-produced material in the world, and simply making it produces as much as 9% of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions,” Tour said. “If we can use less concrete in our roads, buildings and bridges, we can eliminate some of the emissions at the very start.”

According to Rice University, recycled tires are already used as a component of Portland cement, but graphene has been proven to strengthen cementitious materials, concrete among them, at the molecular level.

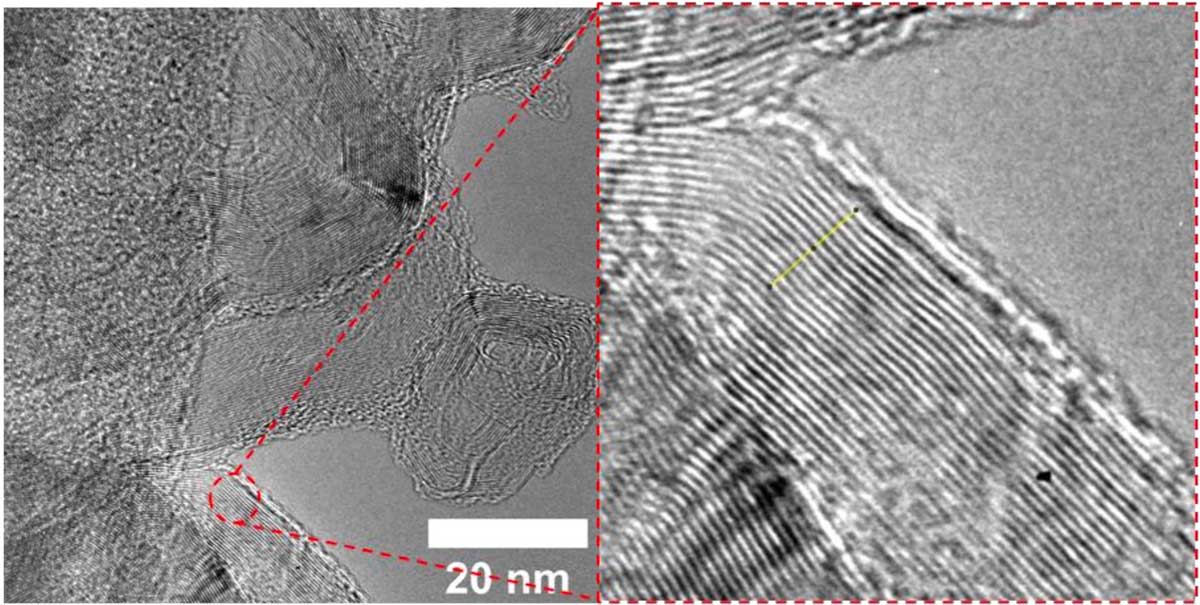

A transmission electron microscope image shows the interlayer spacing of turbostratic graphene produced at Rice University by flashing carbon black from discarded rubber tires with a jolt of electricity. Courtesy of the Tour Research Group. | Graphics by Rice University.

While the majority of the 800 million tires discarded annually are burned for fuel or ground up for other applications, 16% of them wind up in landfills.

“Reclaiming even a fraction of those as graphene will keep millions of tires from reaching landfills,” Tour said.

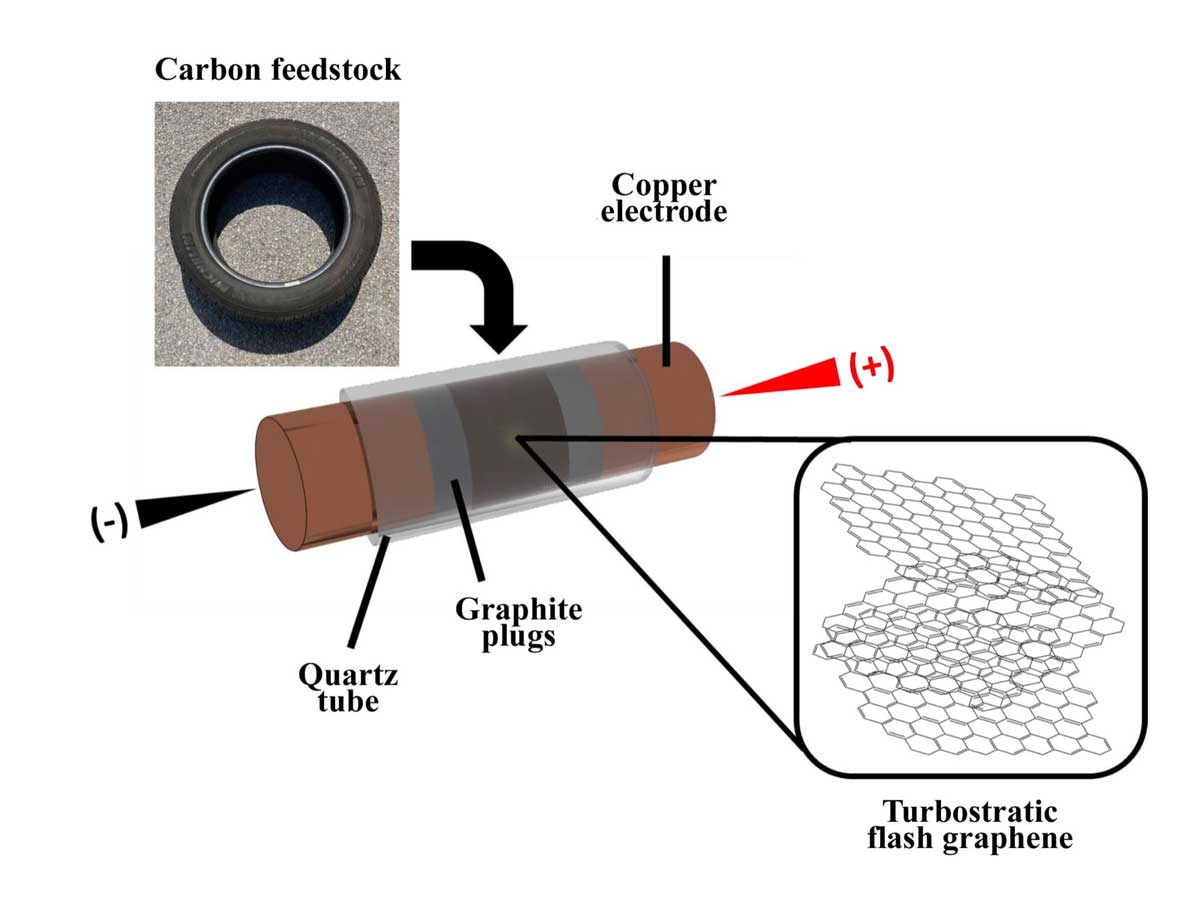

The “flash” process introduced by Tour and his colleagues in 2020 has been used to convert food waste, plastic and other carbon sources by exposing them to a jolt of electricity that removes everything but carbon atoms from the sample.

Those atoms reassemble into valuable turbostratic graphene, which has misaligned layers that are more soluble than graphene produced via exfoliation from graphite. That makes it easier to use in composite materials.

Rubber proved more challenging than food or plastic to turn into graphene, but the lab optimized the process by using commercial pyrolyzed waste rubber from tires. After useful oils are extracted from waste tires, this carbon residue has until now had near-zero value, Tour said.

Tire-derived recovered carbon black or a blend of shredded tires and commercial carbon black can be flashed into graphene. Because turbostratic graphene is soluble, it can easily be added to cement to make more environmentally friendly concrete.

The research led by Tour and Rouzbeh Shahsavari of C-Crete Technologies is detailed in the journal Carbon.

Rice scientists optimized a process to turn rubber from end-of-life tires into turbostratic flash graphene. Courtesy of the Tour Research Group. | Graphics by Rice University.

The Rice lab flashed tire-derived carbon black and found about 70% of the material converted to graphene. When flashing shredded rubber tires mixed with plain carbon black to add conductivity, about 47% converted to graphene. Elements besides carbon were vented out for other uses.

The electrical pulses lasted between 300 milliseconds and 1 second. The lab calculated electricity used in the conversion process would cost about $100 per ton of starting carbon.

The researchers blended minute amounts of tire-derived graphene — 0.1 weight/percent (wt%) for tire carbon black and 0.05 wt% for carbon black and shredded tires — with Portland cement and used it to produce concrete cylinders. Tested after curing for seven days, the cylinders showed gains of 30% or more in compressive strength. After 28 days, 0.1 wt% of graphene sufficed to give both products a strength gain of at least 30%.

“This increase in strength is in part due to a seeding effect of 2D graphene for better growth of cement hydrate products, and in part due to a reinforcing effect at later stages,” Shahsavari said.

Rice graduate student Paul Advincula is lead author of the paper. Co-authors are Rice postdoctoral researcher Duy Luong and graduate student Weiyin Chen, and Shivaranjan Raghuraman of C-Crete. Tour is the T.T. and W.F. Chao Chair in Chemistry as well as a professor of computer science and of materials science and nanoengineering at Rice.

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory supported the research.

Original press release by Mike Williams, Rice University.

Weibold is an international consulting company specializing exclusively in end-of-life tire recycling and pyrolysis. Since 1999, we have helped companies grow and build profitable businesses.