Weibold Academy: European Parliament adopts revised rules governing shipments of waste

Weibold Academy article series discusses periodically the practical developments and scientific research findings in the end-of-life tire (ELT) recycling and pyrolysis industry.

This article is a review by Claus Lamer – the senior pyrolysis consultant at Weibold. One of the goals of this review is to give entrepreneurs in this industry, project initiators, investors and the public, a better insight into a rapidly growing circular economy. At the same time, this article series should also be a stimulus for discussion.

For the sake of completeness, we would like to emphasize that these articles are no legal advice from Weibold or the author. For legally binding statements, please refer to the responsible authorities and / or specialist lawyers.

Introduction

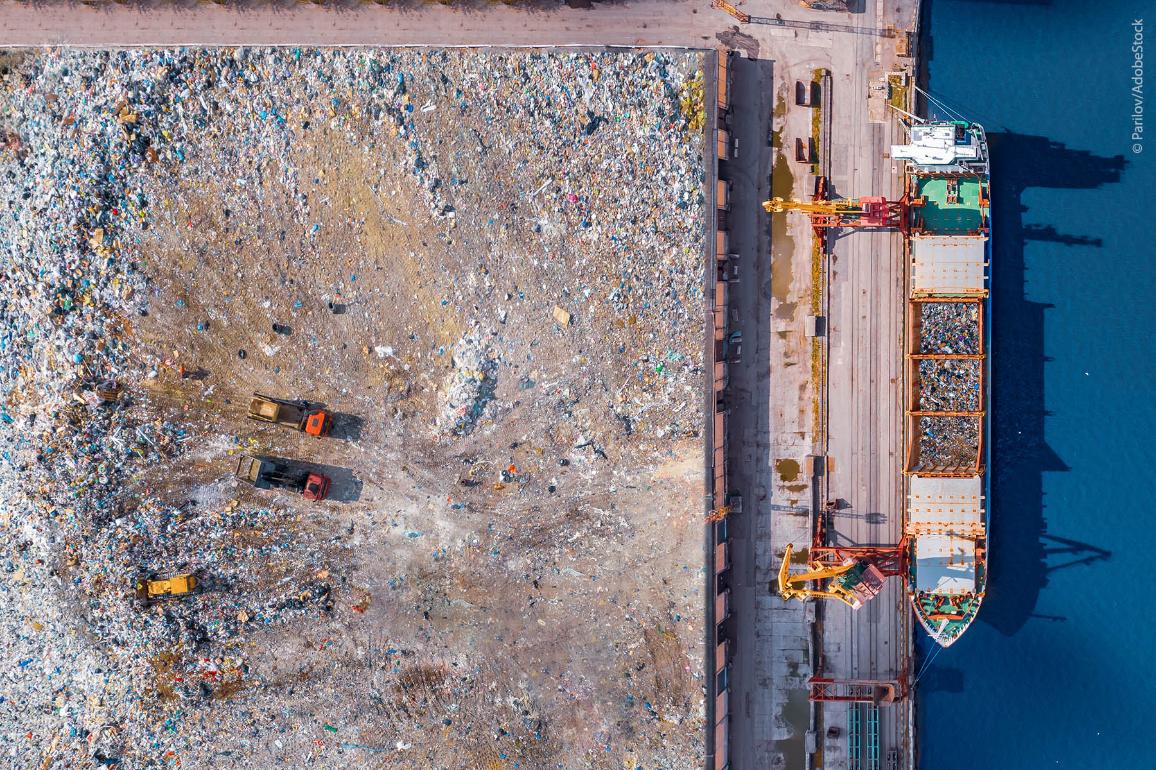

In 2018, global trade in waste reached 182 million tonnes with a value of around EUR 80.5 billion. Such trade has increased considerably in the last decades, with a peak of nearly 250 million tonnes in 2011. The EU is an important player in global trade in waste, and considerable volumes of waste are being shipped between Member States. In 2020, the EU exported to non-EU countries around 32.7 million tonnes of waste, an increase of 75% since 2004, with a value of EUR 13 billion. Ferrous and non-ferrous metal scrap, paper waste, plastic waste, textile waste and glass waste represent most of the waste exported from the EU. The EU also imported approximately 16 million tonnes, valued at EUR 13.5 billion. In addition, around 67 million tonnes of waste per year are shipped between Member States (intra-EU shipments of waste).

Measures on the supervision and control of shipments of waste have been in place in the EU since 1984. In 1989, the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal (Basel Convention) was adopted to address serious problems linked to deposits of toxic wastes imported from abroad to various parts of the developing world. In 1992, the OECD adopted a legally binding decision on the control of transboundary movements of wastes destined for recovery operations (OECD Decision).

In EU law Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006 (Waste Shipment Regulation (WSR)) implements the provisions of both the Basel Convention and the OECD Decision. In certain aspects, the WSR contains stricter control measures than the Basel Convention. The WSR requires Member States to ensure that shipments of waste and their treatment operations are managed in a manner that protects the environment and human health against any adverse effects that might result from such wastes.

The Waste Shipment Regulation has been amended several times since 2006. In 2014, the most recent changes required Member States to draw up control plans. This amendment also included the requirement for the Commission to carry out a review of the regulation by 31 December 2020. In preparation for this review, a comprehensive assessment was carried out, including a public targeted consultation and a mandate for an external study.

Source: European Parliament.

The overall objective of the WSR review is to increase the level of protection of the environment and public health from the impacts of unsound transboundary shipments of waste. It addresses the problems identified in the WSR evaluation published by the Commission in January 2020.

The WSR revision also responds to the call under the European Green Deal and the Circular Economy Action Plan to revise the WSR with the aim of:

- facilitating shipments of waste for reuse and recycling in the EU;

- ensuring that the EU does not export its waste challenges to third countries; and

- tackling illegal waste shipments.

Moreover, the European Green Deal and the Industrial Strategy, including its update acknowledged that access to raw materials is of strategic importance and a pre-requisite for Europe to deliver on its green and digital transition. The Critical Raw Materials Action Plan stressed that significant amounts of resources leave Europe in the form of wastes, instead of being recycled into secondary raw materials and thus contributing to the diversification of sources of supply for the industrial ecosystems in the European Union.

The European Parliament and the Council have also invited the Commission to come forward with an ambitious revision of the Waste Shipment Regulation.

Lack of effectiveness

The Waste Shipment Regulation created a solid legal framework that was implemented by the Member States. In general, it improved the control of waste shipments and contributed to the environmentally sound treatment of shipped waste at national and EU level.

However, its optimal implementation across the EU has been hampered by the fact that it is applied and enforced at different levels and in different forms - often with different interpretations of its provisions and different control regimes. These factors mean that there is little or no legal transport of high-value waste to appropriate recycling facilities, despite these being important for the transition to a circular economy in the EU.

Regarding the export of waste, and particularly non-hazardous waste, from the EU, the lack of control over the conditions under which this waste is treated in the countries of destination, and particularly in developing countries, is a major shortcoming.

Illegal shipments of waste in and out of the EU also remain a significant problem because the provisions of the Waste Shipment Regulation are general (namely in relation to the elements that competent authorities need to control, e.g., related to the environmentally sound management of waste, and enforcement). Other causes are deficiencies in the application and enforcement of the Waste Shipment Regulation.

Lack of efficiency

The main obstacles to the efficient implementation of the Waste Shipment Regulation are the complex, time-consuming notification procedures (often on paper) and the different interpretations of the classification of waste by Member States. The focus here is on the question of what is waste and what is not and what is to be regarded as hazardous and non-hazardous waste. For economic operators who want to ship waste inside or outside the EU, this can result in cumbersome procedures.

The lack of a common interpretation of the Waste Shipment Regulation leads to delays in the shipment. Until decisions are made, these delays can result in additional costs for (e.g.) storing the waste.

Suitable only to a limited extent

The original objectives of the Waste Shipment Regulation (to protect the environment and human health from the adverse effects of waste shipment and to implement the Basel Convention and the OECD Decision) are still of great importance for the EU.

The rules on shipments of waste are also relevant for the transition to a circular economy. However, the Waste Shipment Regulation was not designed to facilitate the transition to a circular economy, as circular economy only emerged as a new overarching EU policy priority after the adoption of the Waste Shipment Regulation.

Lack of coherence

The Waste Shipment Regulation is not fully coherent with EU circular economy policy.

A particular inconsistency between the Waste Framework Directive and the Waste Shipment Regulation is that the latter does not contain provisions that would prioritize shipment for recycling over other forms of recovery (e.g., incineration with energy recovery) and support the implementation of the waste management hierarchy.

There is a certain coherence between the Waste Shipment Regulation and the Basel Convention and the OECD decision. For the authorities and actors involved in the shipment of waste, however, the situation is complicated by the fact that different classification codes are used in different frameworks (Basel, OECD, EU list of waste, customs law).

Furthermore, the way in which the Basel Convention and the OECD decision have been implemented in the EU through the Waste Shipment Regulation limits the EU's ability to regulate intra-EU shipments.

Targets of the revised and amended WSR

On 17 November 2021, the Commission tabled a proposal to reform the EU rules on waste shipments, laying down procedures and control measures for the shipment of waste, depending on its origin, destination and transport route, the type of waste shipped, and the type of waste treatment applied when it reaches its destination.

The Environment Committee adopted its position on revised rules governing shipments of waste to boost the EU circular economy, resource efficiency and zero pollution goals on December 1st, 2022.

- Better information exchange and transparency on shipments within the EU and to explicitly prohibit shipments within the EU of all wastes destined for disposal, except if authorised in limited and well-justified cases. Uniform criteria for the classification of waste shall ensure that the rules are not circumvented by clearly distinguishing, for example, between used goods and waste. The new rules shall include digitalising the exchange of information and documents within the internal market. Storing information in a central electronic system would improve data reporting, analysis and transparency.

- Strengthening the rules governing exports of waste outside the EU. Exports of hazardous waste to non-OECD countries shall be prohibited. Else, EU exports of non-hazardous waste for recovery shall be allowed only to those non-OECD countries that give their consent and demonstrate their ability to treat this waste sustainably. The Commission will draw up a list of such recipient countries, to be updated at least every year. The Commission would also monitor waste exports to OECD countries more closely to ensure that they manage waste in an environmentally sound manner as required by the rules and that they do not adversely affect the management of domestic waste in that country.

- Reinforcing prevention and detection of illegal shipments. The Committee calls for the creation of an EU risk-based targeting mechanism to guide EU countries that carry out inspections to prevent and detect illegal shipments of waste.

Selected impacts (expected) of the revised and amended WSR

In terms of overall economic impact, the revised and amended WSR should result in significant savings for operators shipping waste and for authorities dealing with the procedures for authorising and monitoring these shipments, notably thanks to the establishment of the electronic data interchange system. This is expected to deliver savings in the order of EUR 1.4 million a year. Other measures to modernise and simplify the WSR will bring additional savings.

Another important economic impacts shall come from the measures linked to the export of waste, which should represent an overall economic gain for the EU economy, based on 2019 data, ranging from EUR 200-500 million a year, depending on the amount of waste that is retained in the EU.

For economic operators based in the EU, the impacts of these measures shall differ significantly depending on their position in the value chain and the types of waste concerned. Some of those involved in exporting these wastes are likely to see the costs for exporting such waste increasing, or they would turn to other purchasers in the EU, where they might get lower prices for their waste. Companies exporting waste would also have to set up (or purchase) auditing schemes to verify that facilities in third countries perform waste management activities in a sustainable manner; this would represent new but moderate costs.

On the other hand, economic operators recycling or processing waste in the EU may be able to use more waste as feedstock, which they should be able to purchase at a lower price compared with the baseline. The measures on illegal shipments should benefit legal operators as they will help to tackle illegal activities; these represent a direct competition to the business of legal operators.

For companies located in third countries which transport, and process waste imported from the EU, the effect would be positive for those performing their activities in an environmentally sound manner, as the audit would consolidate their activities and competitiveness, even though it could also incur some costs for upgrading their infrastructure and standards in the short term. The impact would be negative for those companies which are not able to comply with the criteria for environmentally sound management of waste laid out in the auditing schemes as they would lose customers from the EU.

SMEs will benefit greatly from the measures designed to facilitate shipments of waste within the EU. The obstacles and burdens linked to the shortcomings of current procedures represent proportionally a heavier burden for them than for larger companies. The measures on the export of waste will affect SMEs involved in export-related business activities. They will incur new costs to perform audits in facilities to which they are shipping their waste. These costs, however, remain limited and could be pooled with other SMEs, notably through Producer Responsibility Organisations. Finally, the perspective that more waste will remain in the EU, together with new targets and obligations under EU law to ensure its recycling, will also represent opportunities for SMEs to develop innovative projects and technologies for recycling waste whose treatment poses challenges, such as plastic and textile waste.

This preferred option is expected to result in an overall significant positive environmental impact. The measures designed to facilitate the shipment of waste for re-use and recycling in the EU will lead to higher amount of waste treated in better environmental conditions. They would also lead to higher amounts of secondary materials available in the EU, which would replace virgin materials as feedstock for several industries based in the EU. The proposed measures relating to the export of waste would have positive environmental impacts as they would better guarantee that shipments of waste to third countries are managed in an environmentally sound manner. It would also potentially lead to between 2.4 and 6 million tonnes of waste being retained in the EU each year, which would be treated according to EU standards and processed into secondary materials. While it is not possible to perform a monetised impact of all these environmental gains, the benefits linked to a better treatment of residual waste in the EU and to avoiding shipping this waste to third countries would range from EUR 250 to 650 million a year. The overall gains are likely to be even higher. By contributing to improving the overall effectiveness and efficiency of the enforcement regime, the measures relating to illegal shipments would help prevent and reduce the serious environmental impacts stemming from illegal waste shipments, bringing overall environmental benefits.

Finally, as regards the overall social impact, the measures linked to the export of waste, and to those against illegal shipments of waste, should reduce the negative impact on human health (e.g. respiratory problems, injuries) and labour conditions (e.g. no social benefits, low wages) stemming from the unsustainable management of waste, bringing overall benefits to society both abroad and in the EU. The treatment in the EU of waste that used to be exported should lead to the creation of 9,000-23,000 jobs in EU recycling and re-use sectors. Additional jobs in these areas are likely to be generated because of the measures designed to ensure a better functioning of the WSR for shipments of waste in the EU for recycling and re-use. In third countries there might be job losses in the formal or informal waste treatment sectors in case less waste is exported to that country.

Amendments adopted by the European Parliament on 17 January 2023

Finally 150 amendments have been adopted by the European Parliament on 17 January 2023 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on shipments of waste and amending Regulations (EU) No 1257/2013 and (EU) No 2020/1056 (COM(2021)0709 – C9-0426/2021 – 2021/0367(COD)).

Among this large number of amendments there are some that are important for achieving CE goals and which can give the recycling industry an important boost:

- It is necessary to lay out rules at the Union level to protect the environment and human health against the adverse impacts which may result from the shipment of waste. These rules should also contribute to the facilitation of environmentally sound management of waste, in accordance with the waste hierarchy laid down in Article 4 of Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, as well as to the reduction of overall impacts of resource use and to the improvement of the efficiency of such use, which is crucial for the transition to a circular economy and for reaching climate-neutrality by 2050 at the latest. In this regard, waste management should be considered as one step of the product life cycle spanning from production to secondary raw materials, for which sustainable innovative techniques which seek to improve material recovery, energy efficiency, and waste management’s overall contribution to decarbonisation should be prioritized. (Recital 1)

- The European Green Deal sets out an ambitious roadmap to transform the Union into a sustainable, resource efficient and climate neutral economy. It calls on the Commission to review the Union rules on waste shipments established under Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006. The New Circular Economy Action Plan adopted in March 2020 further stresses the need for action to ensure that shipments of waste for re-use and recycling in the Union are facilitated, that the Union does not export its waste challenges to third countries and that illegal waste shipments are better addressed. In addition to the environmental and social benefits, this can also result in ameliorating EU’s strategic dependencies on raw materials. Keeping more of the generated waste within the Union will, however, require improved recycling and waste management capacity. Both the Council and the European Parliament have also called for a revision of the current Union rules on waste shipments established under Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006. To support the circular economy, innovative business initiatives such as taking back waste for the purpose of recycling, refurbishment, research or for improvement of product design should be supported. (Recital 3)

- Research and innovation should be an integral part of the European waste management sector. The research and innovation network for waste should include industry, universities, and other research institutions. (Recital 10a)

- To ensure a real transition towards a circular economy for shipments of waste from its place of origin to the best place of treatment for such waste, the principle of proximity, material efficiency as well as the need to reduce the environmental footprint of waste should be considered. (Recital 10b)

- This regulation should provide legal certainty and ensure uniform application of Union legislation within the area of waste management to facilitate compliance with the relevant provisions on protection of the environment and human health. Creating an undue administrative burden, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises, should be avoided. (Recital 11a)

- To take account of innovation in waste treatment technologies with regard to environmental sound management. (Recital 16a)

Unlike the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union is not yet ready to enter trialogue talks on the revision of the EU Waste Shipment Regulation (WSR). 2022, the Council's Working Party on the Environment had primarily focused on rules governing transboundary shipments of waste between EU member states during five meetings. According to an update provided by the Czech government at the Environment Council meeting shortly before Christmas 2022, several general clarifications had also been sought under the Czech EU Presidency on the relationship between the WSR proposal and international agreements such as the Basel Convention. This means that closer examination of the proposed changes to the rules for exports to third countries, both to OECD states and to non-OECD member countries, must still be carried out. This work will now be led by Sweden, which took over the rotating EU presidency at the beginning of the year. The WSR is on the agenda for today's meeting of the Council's Environment Working Party. (Source)

Conclusion

A well-functioning Union market for waste shipments should prioritise proximity, self-sufficiency, and the use of the best available techniques in waste management as guiding principles. Achieving a fair transition to a circular economy is essential to attaining a climate neutral, resource-efficient, and competitive Union economy that is sustainable in the long run.

Without an EU-wide regulation of transboundary shipments of waste, EU Member States would simply apply the Basel Convention and the OECD decision. The European Waste Shipment Regulation, which is in its last stages of implementation, provides much more detail, allowing for a more coherent approach, and its environmental requirements are stricter than those of the international instruments.

Once approved, this regulation should prevent further divergence of rules instituted by the European Member States, which would have negative consequences for proper waste management and economic operators.

The Waste Shipment Regulation is adding value to the inter-European waste management and is enabling a circular economy approach in the EU. It should be further explored and developed. There is a strong case for better aligning the objectives of the Waste Shipment Regulation with those of the EU's ongoing transition to a circular economy and ensuring that the Regulation facilitates the most circular waste treatment option.

Sources:

Amendments adopted by the European Parliament on 17 January 2023

Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on shipments of waste and amending Regulations (EU) No 1257/2013 and (EU) No 2020/1056

Waste shipments: stricter rules to protect the environment and human health

Weibold is an international consulting company specializing exclusively in end-of-life tire recycling and pyrolysis. Since 1999, we have helped companies grow and build profitable businesses.